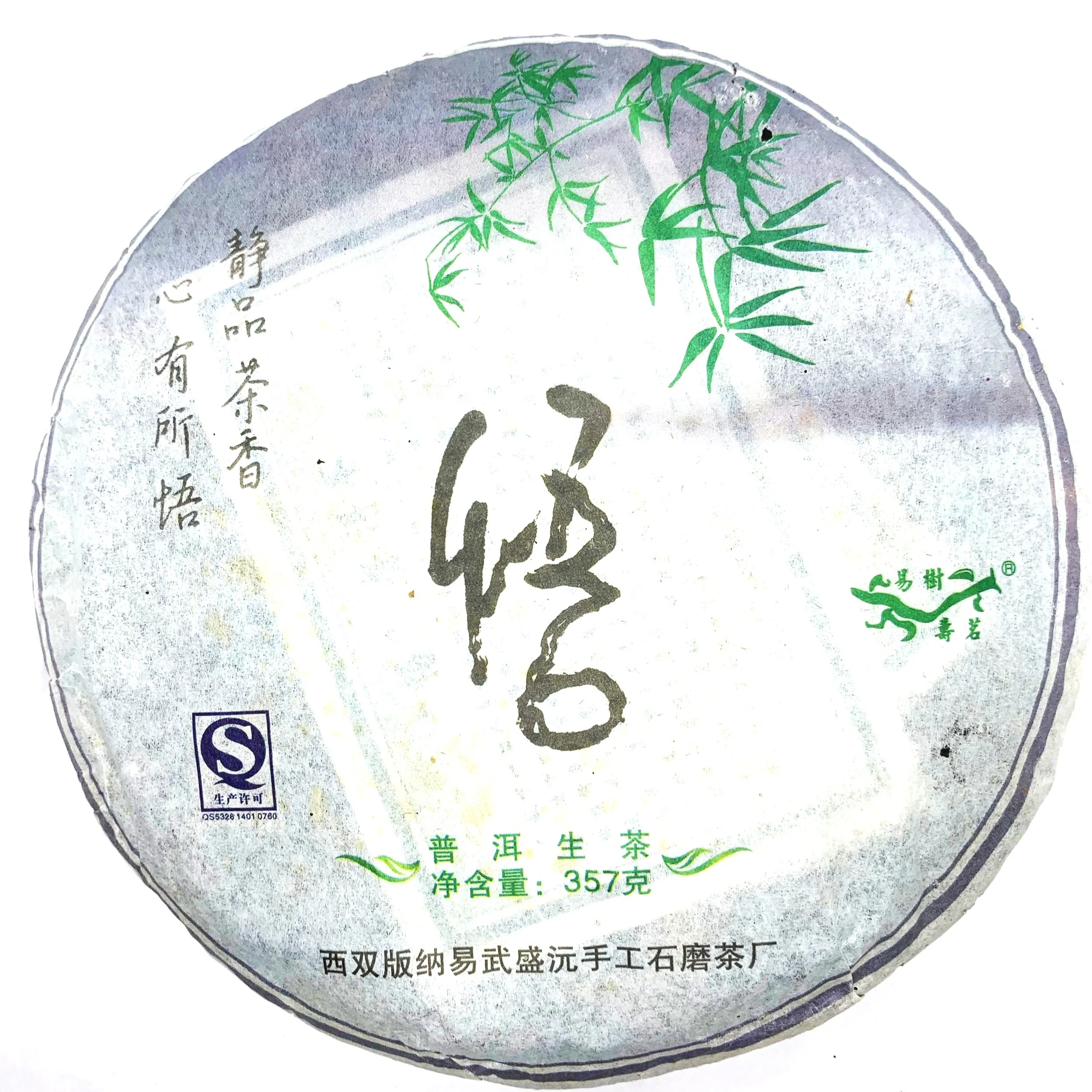

Yiwu Old Arbor (2011)

Yiwu Old Arbor (2011)

The Yiwu mountains in Southern China are renowned for the fragrant, smooth and floral teas they produce. One of the most highly sought after terroirs in the tea world, this blend of old tree material from different villages has aged beautifully in wet Guangzhou storage. This sheng style pu’er tea was made from a blend of old arbor material harvested in the Spring of 2011 from different villages across a somewhat wide area. At 11 years of age, it is sweet and woodsy, drinkable and layered. If you’re looking to experience tea that has both high-quality base material and age, then you’ve come to the right place.

Harvest - Spring 2011

Origin - Yiwu, Yunnan, China

Storage - Guangzhou

Tastes Like - Antique Wood, Dried Peaches, Musky

Sold by the ounce or as a 357g cake

Old Arbor Pu’er

“Old arbor” is called “lao qiaomu” (老乔木) in Chinese. As the name suggests, this Pu’er is made from the leaves of older trees (usually at least older than 100 years, but often much older). Qiaomu (乔木), or “arbor trees,” are also called "big tree tea" (大树茶) in China. These trees are found in natural environments where each tree has space to grow and has also developed deep roots which let it absorb many nutrients and minerals from the soil resulting in a smooth, developed, and complex-tasting tea; even with relatively less aging. Arbor trees are generally more resilient and so generally do not need pesticides or other interventions.

Plantation-style Tea Trees vs Old Arbor and Ancient Trees

Pu’er grown from plantation-style tea trees, called “taidi” Pu’er (台地普洱), is the most common Pu’er on the market. When demand for Pu’er tea increased in the 1980s, many gardens were created to meet demand and were planted with dense rows of tea trees on plateaus or hillside terraces. The tea trees are kept small and are usually younger than 10 years of age. The gardens produce a high yield but usually require fertilizers and pesticides.

Old arbor “lao qiaomu” (老乔木) and ancient tree “gu shu” (古树) Pu’er come from older trees found in natural environments with diverse ecologies. These larger tea trees don’t yield as much per unit area, but are generally considered to produce higher quality teas. These trees have deep roots that absorb many minerals from the soil resulting in teas that have a more nuanced taste and a better tea energy (“cha qi” 茶气). In their natural environment, these trees grow symbiotically with other plants, and in such a balanced ecological environment there is no need for fertilizers or pesticides. While it may not be exactly defined, often the term “gu shu” (ancient tree) is used to refer to the oldest tea trees, and “qiaomu” (乔木, arbor trees) are typically aged somewhere between “gu shu” ancient trees and the younger, plantation-style tea trees.

Pu’er Tea Blends (普洱茶拼配)

Much of the Pu’er tea sold on the market are “blends'' (拼配普洱茶) of multiple different Pu’er teas. The opposite of a blend would be what is called “pure” Pu’er (纯料普洱). The exact definition of these terms may vary. For example, the most “pure” a single Pu’er could be would seem to be one in which the tea leaves were plucked not only from the same region or garden and at the same time, but even from the same tree (although this may not always be practical due to limited resources). Blends can therefore combine tea leaves from different batches of tea that may be from different regions and/or different harvest dates. There is something special about a “pure” Pu’er in that you can fully experience the character of a particular location and/or season. On the flip side, blends, if done well, can create complex and refined products that can balance the strengths and weaknesses across many individual “pure” Pu’ers while also offering practical benefits to the tea producers.

There are several types of Pu’er blends, including:

Tea Mountain “Cha Shan'' Blend (茶山拼配): There is a saying among Pu’er enthusiasts, “red wine goes by the winery, Pu’er goes by the mountain” (红酒看酒庄,普洱看山头). There are many tea mountains in Yunnan and each has its own unique terroir. Some may tend more towards bitterness and astringency while others more towards a sweet and mellow flavor profile. Blends of Pu'er from different tea mountains have the potential to balance these aspects and create a complex and interesting result.

Seasons Blend (季节拼配): Yunnan tea is generally picked in the three seasons of spring, summer, and autumn. Usually, the spring tea is considered the highest quality, but it also demands the highest price. Blending teas of different seasons can improve the quality of teas available in certain seasons (or reduce it, depending on how you look at it), and can level out the pricing.

Grade Blends (等级拼配): Pu’er tea is divided into 11 grades with the lowest quality including rougher tea leaves and therefore a rougher taste. Blends can mix tea leaves of different grades together to neutralize undesirable qualities.

Year Blends (年份拼配): Young Pu’er teas can have much more bitterness and astringency than older, aged Pu’ers. To balance this and other qualities such as color, aroma, and mouthfeel, aged tea leaves can be mixed in with younger leaves. Often, the percentage of “old material” does not exceed 10%.

Tea Tree Type Blends (树种拼配): A type of blending that has emerged in recent years combines tea leaves from different types of tea trees, for example, blending ancient tree “gu shu” (古树) leaves with plantation bush “tai di” (台地) leaves. Generally the amount of ancient tree material is between 20-50%.

Blending based on specific characteristics (茶性特点拼配): Many characteristics can be taken into account when choosing tea leaves for a blend such as altitudes, soil types, and other ecological factors that affect how the tea trees grow. The best blends will not be a random mix and match but will intentionally consider the various characteristics of each tea leaf material chosen. Likely, this method is included along with the other categories of blends above. Each category is not static and can be combined with the others.

Yiwu Tea Area (易武茶区)

Yiwu is one of the most prized tea areas in Yunnan. There is a saying “Ban Zhang Wang, Yiwu Hou'' (班章王,易武后), which means “Ban Zhang is the king, Yiwu is the Queen.” The statement is meant both to recognize two of the best tea areas and also to say something about the taste and character of the tea from each. Yiwu is said to be the “Queen” because the tea from Yiwu often has a delicate, floral, smooth, and gentle taste. The Yiwu tea area is large and consists of the "Seven Villages and Eight Strongholds'' (七村八寨). The Seven Villages refers to Mahei (麻黑), Gaoshan (高山), Luo Shui Dong (落水洞), Manxiu (曼秀), San Heshe (三合社), Yibi (易比), and Zhang Jiawan (张家湾). The Eight Strongholds are Yao Dingjia Zhai (丁家寨/瑶族), Han Dingjia Zhai (丁家寨/汉族), Jiumiao (旧庙), Luode (倮德), Dazhai (大寨), Mansa (曼撒), and Xinzhai (新寨). Additional details on some of these areas are included below:

Gua Feng Zhai (刮风寨) - The “Windy Village” located near the border between China and Laos with pristine, un-touched tea tree forests. Gua Feng Zhai tea is considered to be some of the best in the Yiwu area. Our Gua Feng Zhai Gushu Pu’er can be found here.

Dingjia Village (丁家寨) - A village that has two sections - one populated mostly by Han Chinese and the other by Yao ethnic minority. Most of the famous Pu’er tea from this area is picked and made by the Yao people.

Luo Shui Dong (落水洞) - A village of only 33 households (roughly 120 people) that has a cave with a large water “sinkhole” at the center which connects to nearby rivers via underground currents.

Daqi Shu (大漆树) - Located in Mengla County, this area is populated mostly by Han Chinese. It is rumored that the origin of its name is related to three "lacquer trees." Daqi Shu and Mahei tea gardens are almost connected, and there are a few ancient tree teas in the barren hills of the area.

Zheng Jia Lianzi (郑家梁子) - This is the current name for what was Huantian Village (荒田村). The locals call it "Lotus Pond" (荷花塘). Zheng Jia Lianzi is one of the few Han villages in the Yiwu area. The tea in this production area is mainly unpruned big tree tea coming from high altitude gardens that are in optimal ecological settings. The tea is consistently high quality.

Yi Shan Mo (一扇磨) - This tea area is connected to Paxihe Village (帕溪河村) which consists of about 40 households. The ancient trees in this area are more than 100 years old, and the ecological environment is impeccable. It is a prominent representative of the Mansa tea area, and the output of tea is relatively small.

Mahei (麻黑) - Mahei is one of the villages with the longest history in Yiwu. It is a village dominated by Han people. The handmade tea making techniques handed down from the ancestors have been followed there. Mahei tea trees are full of vitality all year round. The trees grow early each season and have a particularly strong ability to grow buds. Our Mahei and Gaoshan Gushu Blend Puer can be found here.

Gaoshan Zhai (高山寨) - The village is entirely populated by the Yi ethnic minority and is located in Yiwu Township, Mengla (勐腊) County. It is neighbors with Manxiu Village. This tea area has its own unique microclimate. There are a large number of ancient tea gardens in Gaoshan Village. The tea trees are very tall and need to be climbed in order to pick fresh tea leaves from them. Our Gaoshan and Mahei Gushu Blend Puer can be found here.

Walong (瓦竜) - Walong belongs to the Man Zhuan (蛮砖) Tea Area. It is the only production area of extra-large leaf species in the six ancient tea mountains. A total of 30 families in Walong have made tea for their livelihood for generations.

Tea History of Yiwu

Yiwu (易武) has a long history of tea planting and tea making with more than 200 years of glory in the tea industry. It has come to be known as one of the birthplaces of the most profound Pu'er tea culture.

In the Tang Dynasty, tea cultivation began in Yiwu, along with the other six major tea mountains in Xishuangbanna (西双版纳), under the jurisdiction of Yinsheng Prefecture (银生府), corresponding to the present-day ancient city of Yinsheng.

In the Ming Dynasty, with the introduction of advanced processing technology into Chashan, the local tea trade developed unprecedentedly.

During the Yongzheng (雍正) and Qianlong (乾隆) years of the Qing Dynasty, some tea mountains, with Yiwu as the core, developed rapidly and reached a peak period where thousands of people were entering the mountains to make tea. This period stretched from the time of the Daoguang Emperor to the Republic of China.

At that time, Yiwu District and Yibang District produced more than 100,000 catties of tea annually, and were designated as tribute tea production areas by the imperial court. Tribute tea was shipped to Beijing every year. In order to strengthen the management of Yibang (倚邦), Yiwu (易武) and other tea mountains, Qing Dynasty official Ertai (鄂尔泰) set up Qianliang Tea Offices in Yiwu, Yibang, Cheli (车里) and other places.

In 1845, in order to facilitate the tribute tea, Pu'er House (普洱府), the name at the time for what is presently called Pu’er City, built a stone road with a width of six feet and a length of 240 kilometers using government funding. It was paved from Yiwu through Yibang to Pu'er. This road was the origin of the famous "Tea Horse Road" (茶马古道). After that, merchants and caravans gathered in the Yiwu area, and it became the largest tea-making center and trade distribution center among the six major tea mountains in the Pu'er Prefecture.

At that time, there were more than 20 big tea names in Yiwu, famous at home and abroad, some of which had established business names in Hong Kong, Thailand, Vietnam, and other overseas countries. Yiwu tea was supplied to the whole Southeast Asian market and continues to be one of the most popular Pu’er tea regions today.

Yiwu Ancient Town: The Source of The Ancient Tea Horse Road

The Ancient Tea Horse Road was an ancient trade route between Yunnan, Sichuan, and Tibet. Tea from Sichuan and Yunnan was transported by caravans and traded for horses and medicinal materials from Tibet. It was given the name “Cha Ma Gu Dao” (茶马古道), which translates to "Ancient Tea-Horse Road."

At that time, the Pu'er tea produced in Yiwu was exported to Tibet and other areas in Southeast Asia. During the peak tea production season, the number of people who came to purchase and transport tea could reach up to 10,000. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, merchants gathered in Yiwu which made for a lively tea market.

Many horse and cattle caravans passed through Yiwu for trade. The horse caravans were responsible for long-distance transportation, and the cattle caravans were responsible for short-distance transportation. Many road sections of the ancient trade route are still in use around Yiwu today as can be seen from the traces of stone pavement and depressions from horse hooves left in areas where the original road existed.

Pu’er Tea (普洱茶)

Pu’er tea is one of several types of fermented teas (“hei cha” 黑茶, lit. “dark/black tea”) found in China. Fermentation happens in tea as a result of bacteria, yeasts, or other microorganisms breaking down substances in the tea leaves. It is generally initiated by microorganisms indigenous to either the tea leaves or the environment, or by introducing a small amount of starter cultures or already fermented tea leaves.

Pu’er tea is likely the most well-known out of the various types of fermented teas of China. To be considered authentic Pu’er, the tea must have been grown in Yunnan Province from tea plants that are descendants of the Camellia sinensis var. assamica variety of the of the Camellia sinensis tea plant, which is known as Da Ye Zhong (大叶种) in China, meaning “large leaf type.” It must also be sun-dried.

Sheng Pu’er vs Shou Pu’er

Pu’er tea is categorized into either “Sheng” Pu’er (生普洱), meaning “raw” Pu’er, or “Shou” Pu’er (熟普洱), meaning “ripe” Pu’er, depending on the type of processing the tea leaves undergo.

The base material for both Sheng Pu’er and Shou Pu’er is called Pu’er Mao Cha (毛茶) which refers to the “course” or “unfinished” tea leaves that will then be used to create either Sheng or Shou Pu’er tea. The Mao Cha is created from the tea leaves of the large leaf type tea plant that are picked and then undergo withering, pan-firing to “fix” the leaves, rolling, and sun drying. In the fixing step, the leaves are pan-fired at a lower temperature compared to other types of tea so as to retain some of the flavanols responsible for oxidation.

Sheng Pu’er Tea - Sheng (Raw) Pu’er Tea is created by letting the Mao Cha age (oxidize and ferment) naturally over time. It can be sold as loose leaves or compressed into various shapes, such as a cake (bing). Sheng Pu’er can have an astringent taste when young, but the taste will develop with proper aging, becoming enhanced, complex, and smoother. Sheng Pu’ers made from the leaves of old trees (“gu shu'' 古树) are particularly valued.

Shou Pu’er Tea - Also spelled “Shu'' Pu'er, is a type of Pu’er that is created by pile-fermenting the Pu’er Mao Cha leaves. This process is called Wo Dui (渥堆) in China, which means “wet piling.” This process was developed in 1973 as a way to create a Pu’er similar to that of a very old, slow-aged, Sheng Pu’er, but in a fraction of the time. The process is similar to composting. The Pu’er Mao Cha is piled, and then additional moisture is added and wet burlap cloth is placed to cover the pile. The pile is turned occasionally for a period of around 45 days before being dried, sorted, and either pressed into a shape or sold as loose leaves.

Famous Tea Mountains of Xishuangbanna in Yunnan

The tea mountains that made Pu’er tea in Yunnan famous are located in Xishuangbanna prefecture and are divided into two groups: the “Six Great Ancient Tea Mountains” and the “Eight Great New Tea Mountains.” In terms of geographical location, the division is based on the Lancang River: the ancient six tea mountains are located to the northwest of the Lancang River, and so are also called the "North of The River Six Tea Mountains" (江北六大茶山) or the "Inside the River Tea Mountains" (江内六大茶山). The new eight tea mountains are located to the southwest of the Lancang River, and so are also called the "South of the River Eight Tea Mountains" (江南八大茶山) or the "Outside the River Tea Mountains" (江外八大茶山).

Yunnan Xishuangbanna Schematic Diagram of Ancient Tea Mountains (云南西双版纳古茶山示意图)

Pu’er Tea History

Yunnan Province, the home of Pu’er tea, is often recognized as the area where tea trees originated. As far back as 1066 BC, there is evidence in Chang Qu’s (常璩) “Huayang Guozhi” (华阳国志) that tea was used as a tribute for King Wu of Zhou. There is historical evidence that of the eight tribes in the area at that time, the Pu people (濮人) (ancestors of the Bulang people) cultivated tea. Although it was not called Pu’er at the time, ancient farmers in the Yunnan region have long harvested leaves from native large-leaf tea plant variety which they dried in the sun.

In 836 AD, during the Tang Dynasty, records show that tea was popular in the ancient site of Yinsheng (银生) which is presently Jingdong County (景东县). To this day there are still many ancient tea gardens in Jingdong. At this time the tea from that area was called “Yinsheng Tea.”

During the Tang and Song Dynasties, important trade routes were the Silk Road and the Ancient Tea Horse Road, the latter of which extended down through present day Dali and Pu’er City in Yunnan Province. Nomadic peoples of the North and Northwest were successful in combat due to the fact that they possessed many good horses. Yet they ate diets heavy in meat and lacking vegetables. They discovered that tea could help them digest the oily meats they ate so much of. So a “Tea-Horse Market” developed in which the nomads exchanged their horses for tea, giving both parties something that they needed. It can be said that Pu’er tea would not exist as it does today without the Ancient Tea-Horse Road and the many caravans transporting goods along this route, often trading horses for tea.

During the period of the Dali Kingdom (大理国), the Pu'er area was called "Buri" (步日). In the Yuan Dynasty (元), it was renamed to "Buribu" (步日部), and "Buri" was often written as "Puri" (普日).

In the Ming Dynasty, Xie Zhaozhe (谢肇淛 mentioned the word “Pu’er tea” in his book Dian Lue (滇略). This was the first time the word appeared in a written document.

In the 1950s Yunnan Province established a research institute that planted tea on an area of up to 466,000 mu which produced almost 10,000 tons of tea, but the tea trees were severely damaged during the Great Leap Forward. By 1966, the production exceeded 10,000 tons.

In 1984, Wu Qiying (吴启英), the founder of modern Pu’er, used a modern tea inoculation technique to create fermented Shou (ripe) Pu’er tea in 22 days. This innovation laid the foundation for the mass production of modern-day Shou Pu’er tea.

Pressed Pu’er Shapes

Pu’er was historically pressed to make its transportation convenient. Today, the tea is pressed into shapes for either presentation purposes, aging, and/or creating convenient “single-steep-sized” pieces.

The most common shape of pressed Pu’er tea is called “bing cha” (饼茶) or “tea cake,” which is just as it sounds: the tea leaves are pressed into a disk or cake shape. Bings come in various sizes, the most common being 357 grams which was historically what was used for reasons related to transportation. Historically, bings were wrapped into stacks of seven and covered with a bamboo sheath that is held together with bamboo thread, a package that is called a Tong (筒, lit. “tube” or “cylinder”). Twelve tongs would then be combined into a larger package known as a Jian (件) which weighed around 30 kg. A mule was able to carry around 60 kg, so two Jian (30 kg each) could be mounted to a mule–one on each side.

Other pressed Pu’er shapes include a square shape called fang cha (方茶), a bowl/basket shape resembling a bird’s nest called tuo cha (沱茶), melon-shape called jin gua cha (lit. “golden melon tea” 金瓜茶), and a mushroom shape called jin cha (紧茶).

Pu’er Speculative Trading

Similar to fine wine, certain aged Pu’er teas are known for the unbelievably high prices that they can fetch on the market among tea enthusiasts and investors. Some buyers are even more interested in Pu’er for investment purposes than for the enjoyment of drinking it. Due to wide-spread speculation, Pu’er tea’s popularity exploded and prices shot up in the early 2000s, leading to a bubble in the market that burst in 2007. Prices still go up and down today. Pu’er from certain regions are among the most expensive teas in China. Some very old Pu’er cakes can be found in auctions and are sold for thousands of dollars.

Generally, the high priced Pu’er teas are sold as bing cha (pressed Pu’er tea cake). Due to their value, it is not surprising that there are many counterfeits that appear on the market. To combat this, producers add one or two small labels to the tea cake as certificates of authenticity. A small label, called a Nei Fei (内飞) can be placed slightly within the pressed leaves in a way that would be difficult to remove/replace without damaging the cake. Another label, called a Nei Piao (内票) is placed on top of the tea cake before paper is wrapped around it. The name of the tea and the factory that produced it are added to the paper wrapping.